The Telegraph reports about the NHS:

The number of patients waiting to be admitted for operations or other treatment in June was a quarter of a million higher than in the same month last year, official figures show.

The figures come after a report by Monitor, the NHS regulator, which warned that some trusts were cancelling non-emergency procedures to deal with a higher load of emergency cases, resulting in longer waiting times.

The "referral to treatment" data reveals that waiting lists, which have hovered around 2.5 million patients in recent years, reached 2.88 million in June, the highest level since May 2008.

However, the figures also show that the median waiting time for treatment is currently 5.7 weeks – the same duration as in June 2012.

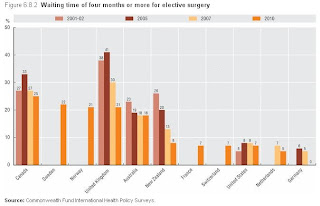

I guess the last paragraph is supposed to represent good news. In the US, when you need surgery, you can get it reasonably quickly. Look at this chart from the OECD for a related statistic, the percentage of people who have to wait four months or more for elective surgery.

Of course, in the US, that's if you have insurance or can otherwise afford the care.

But before you jump to conclusions about the relative gross inequity of that, please note that in the UK, you can get faster treatment if you can afford private insurance or can otherwise pay to go to private clinics or hospitals, where the same doctors who work in the NHS will offer you a different class of treatment.

It might be asserted that the NHS steady-state figures reflect a decision by the government to engage in congestion management to ration care. Based on my experience in the UK, though, the more likely reason for the delays are work flows that are remarkably un-Lean. This is hard to fix, but an example might come from our buddies in Saskatchewan. There, the health authorities adopted the Saskatchewan Surgical Initiative Plan, with a goal of reducing surgical wait times to no more than three months by 2014.

While the results are mixed, the intent is noble, especially when seen in the context of adopting the Lean process improvement philosophy for the entire province.

There's a big difference, of course, in adopting an organizational philosophy for a province of one million people compared to adopting a goal for an organization of 1.7 million people, serving over one million patients every 36 hours!

The process improvement challenges in the NHS represent one of the largest examples I know of a system in need of repair. All I can offer from this side of the Pond is the observation that improvement is likely to come from the individual hospitals and clinics when the central authority of this massive organization understands that its role is to support the development of learning organizations and not to impose arbitrary targets from above.

The number of patients waiting to be admitted for operations or other treatment in June was a quarter of a million higher than in the same month last year, official figures show.

The figures come after a report by Monitor, the NHS regulator, which warned that some trusts were cancelling non-emergency procedures to deal with a higher load of emergency cases, resulting in longer waiting times.

The "referral to treatment" data reveals that waiting lists, which have hovered around 2.5 million patients in recent years, reached 2.88 million in June, the highest level since May 2008.

However, the figures also show that the median waiting time for treatment is currently 5.7 weeks – the same duration as in June 2012.

I guess the last paragraph is supposed to represent good news. In the US, when you need surgery, you can get it reasonably quickly. Look at this chart from the OECD for a related statistic, the percentage of people who have to wait four months or more for elective surgery.

Of course, in the US, that's if you have insurance or can otherwise afford the care.

But before you jump to conclusions about the relative gross inequity of that, please note that in the UK, you can get faster treatment if you can afford private insurance or can otherwise pay to go to private clinics or hospitals, where the same doctors who work in the NHS will offer you a different class of treatment.

It might be asserted that the NHS steady-state figures reflect a decision by the government to engage in congestion management to ration care. Based on my experience in the UK, though, the more likely reason for the delays are work flows that are remarkably un-Lean. This is hard to fix, but an example might come from our buddies in Saskatchewan. There, the health authorities adopted the Saskatchewan Surgical Initiative Plan, with a goal of reducing surgical wait times to no more than three months by 2014.

While the results are mixed, the intent is noble, especially when seen in the context of adopting the Lean process improvement philosophy for the entire province.

There's a big difference, of course, in adopting an organizational philosophy for a province of one million people compared to adopting a goal for an organization of 1.7 million people, serving over one million patients every 36 hours!

The process improvement challenges in the NHS represent one of the largest examples I know of a system in need of repair. All I can offer from this side of the Pond is the observation that improvement is likely to come from the individual hospitals and clinics when the central authority of this massive organization understands that its role is to support the development of learning organizations and not to impose arbitrary targets from above.